Photos: The environmental impact of the Western Qld floods

In many places, floodwater exceeded 1974 levels.

Floods are a natural and periodic part of life in Western Queensland.

They rejuvenate grasses. They spread seeds. They revitalise pastures, wildflowers and soils. They bring waterways, lakes and country “to life”.

But, nearly three months on, the unusual volume and velocity of the 2025 Western Queensland flood event continues to leave its mark.

The environmental impact of the floods

In March and April 2025, unusually widespread and heavy rain fell across Western Queensland and produced flooding that inundated 13 million hectares of the region.

Landholders welcomed the rain as the first decent drop in months, a reprieve at the end of a dryer-than-average wet season that was not looking promising for pasture yield come July.

But then, rain fell and fell.

Floodwaters flow rapidly, tearing up topsoil near Yaraka, as heavy rain continues to fall on March 26, 2025. (Supplied by landholder.)

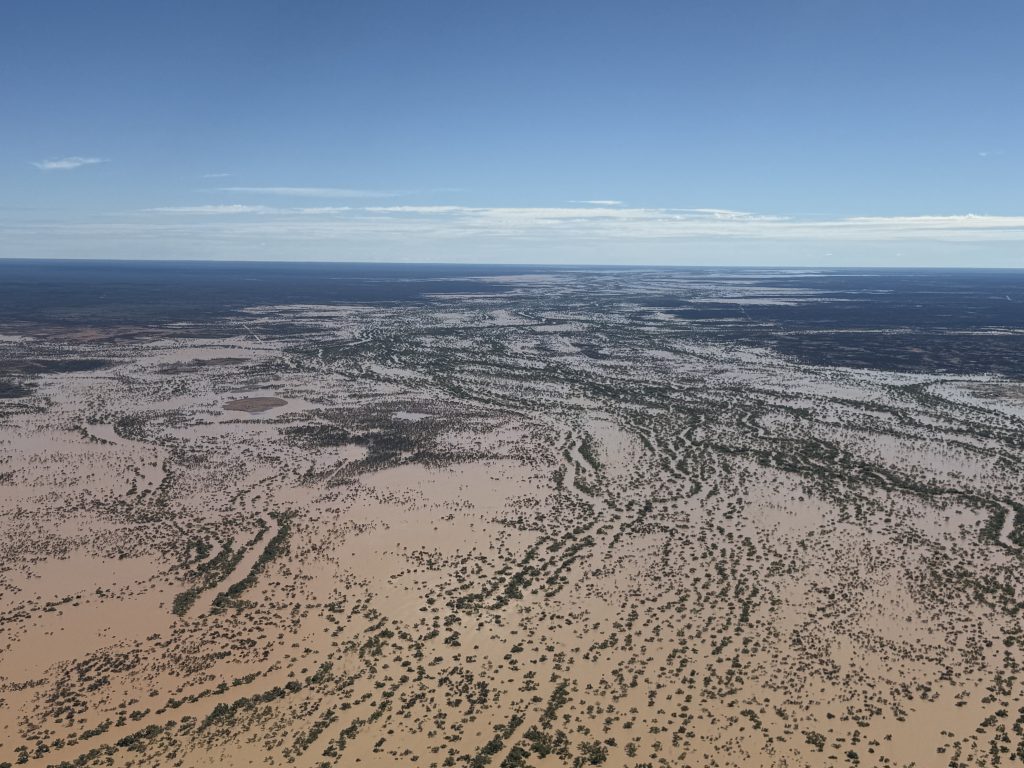

An “inland sea” as floodwaters cut off Windorah from the rest of Queensland on March 29, 2025. (Image by OBE Organic.)

Floodwaters converge between Jundah and Stonehenge on March 30, 2025. (Image by PBE Services.)

Properties saw totals of 300mm. Then 400mm. Then 500mm. By the end of the rain event, some properties had recorded over half a metre of rainfall in just over a week.

For example, Trinidad Station, between Windorah and Adavale, recorded an incredible total of 612mm – nearly double their annual average rainfall – in just nine days.

| Catchment | Area Impacted (Ha) | Notes |

| Cooper Creek | 3.3 million | High impact on all catchment systems |

| Thomson River | 1 million | Bottom third most impacted |

| Barcoo River | 0.66 million | Significant rainfall with scouring in upper catchments and greater flood extent in bottom third |

| Diamantina River | 3.8 million | High impact throughout middle to lower catchment |

| Eyre Creek | 2.6 million | High impact throughout the catchment |

| Georgina River | 1.7 million | High impact throughout the middle to lower catchment |

The impacts of the Western Queensland floods were varied but immediate with landholders bracing for stock losses, damaged infrastructure, destroyed fencing and eroded land.

As floodwaters slowly began to recede, landholders returned to their properties to survey the trail of damage the floods left in its wake.

Some were heartened by the prospect of revitalised pastures and excellent grass bulk, replenished after the extended drink. They would say they got off relatively light, that the flood impact wasn’t “as bad as for them” as “those down south”.

But in the quiet of the paddocks, many knew the impact the floods would have on their operations, their land and their wallet.

Sleeves rolled up, as stockmen and stockwomen got stuck into the task of replacing property and exclusion fencing – essential for keeping the wild dogs out.

Surviving stock were mustered, food supplies were dropped. Trucks decked with hay arrived as choppers took to the skies to feed stranded sheep and cattle with life-saving fodder drops.

Floodwater surrounds Birdsville as upstream flows arrive on April 8, 2025, stretching as far as the eye can see. (Photo by OBE Organics.)

A swollen section of the Diamantina River near Winton begins to recede on March 31, 2025. (Image: Phillip Jackson / Desert Channels Queensland)

The impact on soils

One of the biggest stories following the floods was the stripping of millions of cubic metres of topsoil: that top layer of soil containing seedbank and nutrients required for pastures to grow.

Without topsoil, grass will take decades to grow back.

Landholders near Yaraka, Windorah, Longreach and Quilpie have provided images that show signs of scouring, where that vital layer of soil is now completely gone.

- An estimated 20-40 cms of seed-rich topsoil has been lost in flooded regions, totalling millions of cubic metres.

- Floodwaters dumped this soil as a thick layer of silt/sediment on land downstream, covering more pastures and killing grasses underneath.

- These eroded landscapes will remain bare – contributing to further silting, gully formation, biodiversity loss and waterway degradation in future floods.

The loss of topsoil and silting of pasture and waterways is a devastating double blow for landholders – to sustainability and productivity – and could take decades to restore naturally.

Fortunately, there is a way to speed up the process.

Desert Channels Queensland has developed land restoration techniques in prior floods with a proven “track record” for rehabilitating eroded land.

This technique involves a combination of seeding and monitoring, spelling, fencing, small-scale earthworks and weed control.

We believe this technique should be upscaled to be applied to damaged land to reduce long-term erosion and restore the condition of these soil and pasture resources.

Floodwaters strip topsoil along Acheron Creek, between Stonehenge and Longreach, after 540mm of rainfall. (Image supplied by landholder.)

Silt dumped on wetland between Adavale and Windorah cracks as it dries in April 2025. (Supplied by a landholder.)

Topsoil scouring strips seedbank, nutrients and the vital layer of soil near Windorah in early April , 2025. (Supplied by a landholder.)

Bare, brown country near Yaraka on April 15, 2025 bears the brunt of topsoil scouring and fails to germinate after floods. (Supplied by a landholder.)

Gullies and erosion

Many landholders have reported gully erosion in areas for the first time.

Fast-flowing floodwater tore across floodplains in the Cooper Creek and Thomson River catchments to form gullies of all shapes and sizes.

As the very contours of Channel Country are remolded, these gullies are likely to continue to reshape, grow and expand in future rainfall events.

Although the velocity of this water made gullies more frequent and more pronounced, this is a natural phenomena that will often become the basis for new waterholes and drainage channels⁴.

Landholders survey damage to a property waterhole near Stonehenge on March 29, 2025. (Supplied by a landholder.)

A newly-formed gully near Yaraka photographed on April 15, 2025 after floodwaters reshaped the very contours of Channel Country. (Image supplied by landholder.)

The spread of invasive weeds

An estimated 8.3 million hectares of the Desert Channels region are at risk of weed spread following the 2025 floods, including succulents and woody weeds. Examples include:

- Prickly Acacia

- Parkinsonia

- Rubber Vine

- Parthenium and Sticky Florestina

- Mother of Millions

- Cactus (e.g. Coral, Jumping Cholla, Harissia)

Many of these weeds will hitch a ride in floodwaters to spread seed and start new infestations, spreading down and degrading catchments across the Lake Eyre Basin.

Landholders are recommended to keep an eye on the high-water mark for a year after flood events to deal with any new infestations before they set seed. Always eradicate early to avoid building up a seedbank, which can extend control efforts by up to a decade.

The braided channels of Windorah’s floodplains viewed from the air as water begins to drain on April 9, 2025. (Image by PBE Services.)

Impacts on biodiversity

The cycle of boom and bust continues.

Flocks of birdlife have arrived to take advantage of refilled waterholes across the Desert Channels region – one of the largest breeding bastions for waterbirds in Australia.

Nearly 50 per cent of Australian bird species will migrate to or through the Desert Channels region at some point in the seasonal cycle.

Pelicans and swans remain committed returning visitors.

Pelican flocks frolick along Windorah waterways after the Western Queensland floods on May 15, 2025. (Image: Desert Channels Queensland, Roxanne Blackley)

Feral animals risk

The main pest risks are feral pigs and feral cats. Pest populations were already at medium to high levels, but this flood event has generated a major flush of growth and resources.

Feral cats, in particular, will have climbed trees to avoid the worst of the floodwater and will likely continue to boom in population due to abundant food resources.

Diamantina River floodwater arrives at the Goyder Lagoon in South Australia on April 23, 2025. (Image by Birdsville Aviation.)

Flooding likely destroyed a small percentage of the feral pig population in lower areas of Cooper Creek, Georgina and Diamantina catchments, but these population losses are expected to be quickly made up by the fast breeding rate of feral pigs and the abundance of water and food sources.

- Feral pig control efforts, such as ground baiting, aerial shooting and ground trapping/shooting, should be carried out in the late dry season.

- This is when pigs concentrate around limited water sources.

- Landscape-scale, coordinated, multiple rounds of control within the same breeding cycle is the best way to substantially reduce (85%) feral animal populations.

After peaking at 8.5m, Cooper Creek at Windorah finally drops below the minor flood level after 36 days on May 6, 2025. (Image: Desert Channels Queensland / Phillip Jackson)

¹ McCosker, M. (2025). ABC News. Flooding causes erosion and strips away topsoil in Western Queensland.

² Staff writers. (2025). Courier Mail. ‘Vicious erosion cycle’: Millions of hectares of topsoil impacted by outback flood

³ Marshall, A. (2025). The Land & Queensland Country Life. Bank funds flood in for Rural Aid’s feed, water and welfare work in four states.

⁴ Wakelin-King, G. A. (2022). Landscapes of the Lake Eyre Basin: the catchment-scale context that creates fluvial diversity. Transactions of the Royal Society of South Australia, 146(1), 109–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/03721426.2021.2003514